Nikolas Kaiser

California Baptist University

Professor: Young Seop Lee

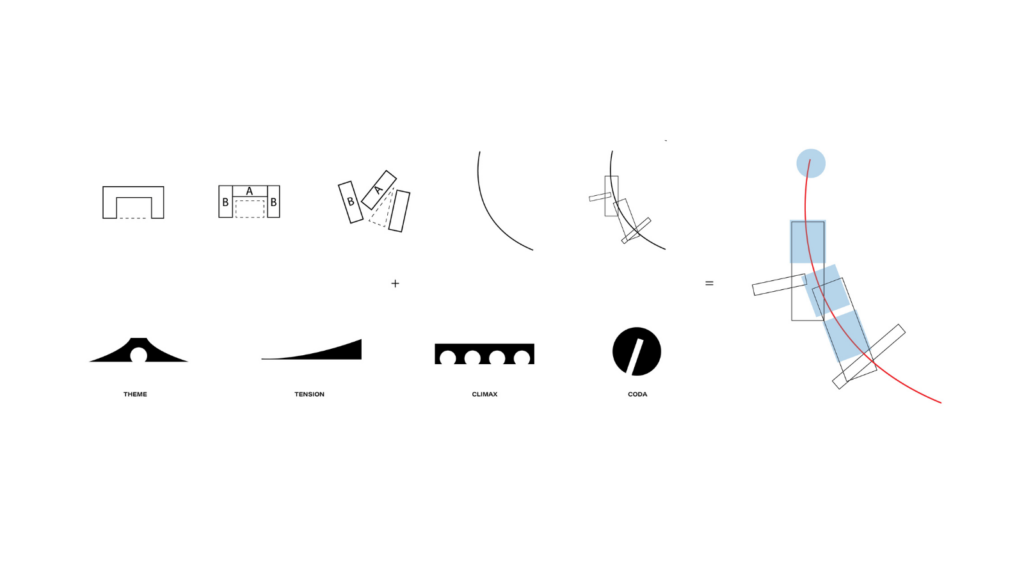

This project is in memory of Dosan Ahn Chang Ho, a Korean independence activist during the Japanese occupation of Korea in 1910. The architecture creates a processional narrative of three ‘acts’, the first being the community centre, followed by the museum and concluding in the memorial lookout. These three acts form a spinal arrangement that follows the shape of the topography and land. Guests experience these distinct environments, with each space abstractly representing different moments in the timeline. The black granite wall symbolises strength and permanence, guiding visitors through its interior and exterior volumes and thresholds, representing Dosan’s leadership and guidance of his people to freedom.”

Procession to Peace – Dosan Ahn Chang Ho Memorial Museum

One of Korea’s most influential leaders, Dosan Ahn Chang-Ho was an independence activist that strived for unity between Japan and Korea during the Japanese occupation of 1910. Dosan was a force for good throughout this conflict, joining a group of Koreans that had left their hometowns and travelled to Riverside, California to find work at the orange groves. Dosan quickly became the leader of this small community, strengthening the will and morale of his fellow Koreans through his teachings and visits to their homes. He stressed the importance of integrity in every action, and helped his people find a new sense of nationalism. His work toward activism inspired many other civil rights movements around the world. This museum seeks to venerate Dosan for his lifelong commitment to peace and freedom in our world, and to teach others about his life’s work and the culture of Korea, his home.

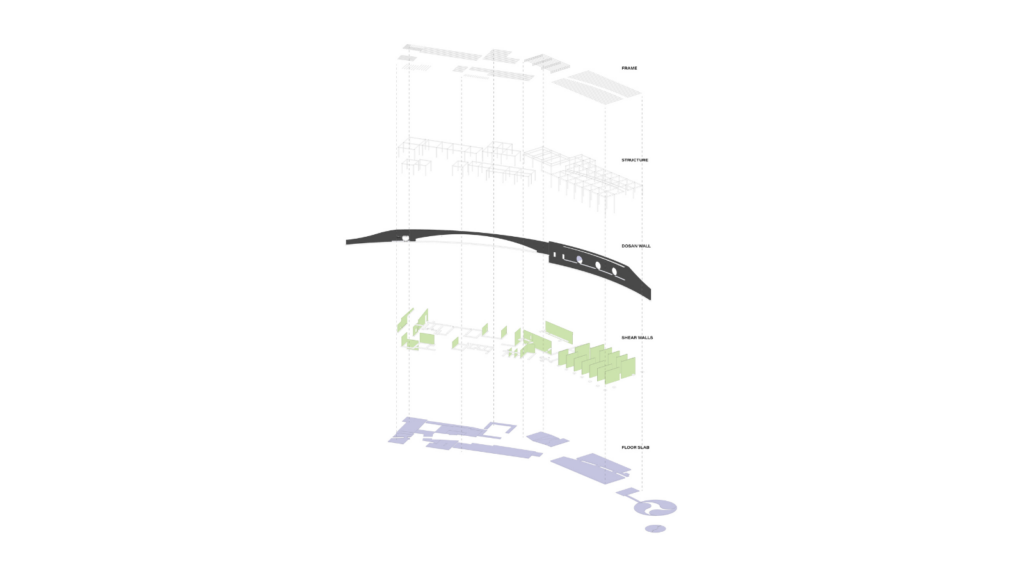

The project is an exploration of how we can use architecture to produce a narrative, structured through symbolism and abstraction. In this case, the architecture looks to the timeline of Dosan’s work for Korean independence. This timeline is visualized by a linear element, a dark granite wall that follows the shape of the landscape, inspired by Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial. The wall is utilized as a symbol of strength and continuity, showing Dosan’s never-ceasing will in his work for Korean independence.

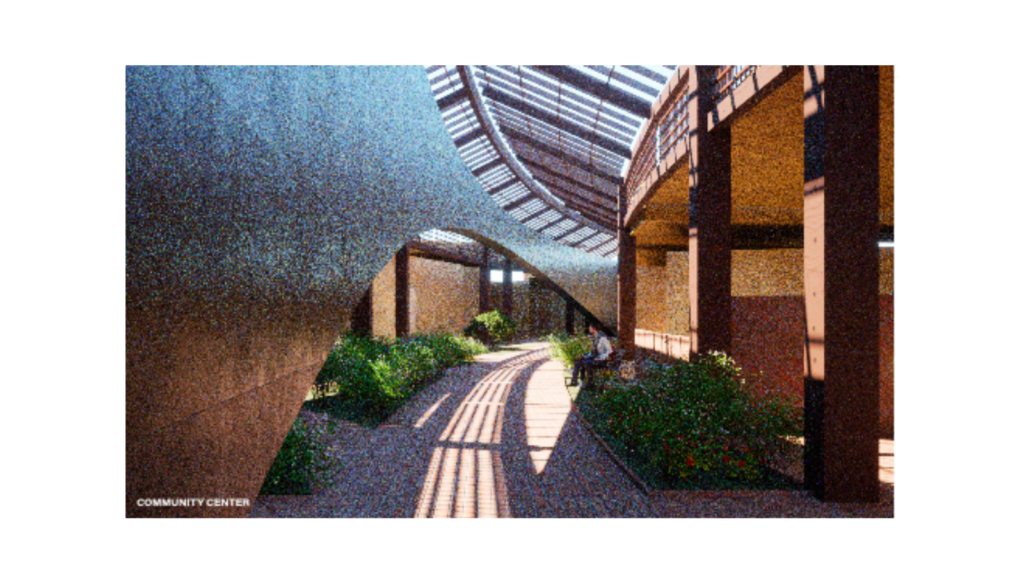

The architecture is arranged around this wall, following organizational principles of the traditional Korean hanok house, a traditional Korean courtyard-style house, to inform the locations of different spaces. The architecture creates a processional narrative of three main places, the first being the community center, followed by the museum and concluding in the memorial lookout. These three places form a spinal arrangement that follows the shape of the topography and land. Visitors enter the project first by passing through the wall in a sequence of one of many thresholds yet to come.

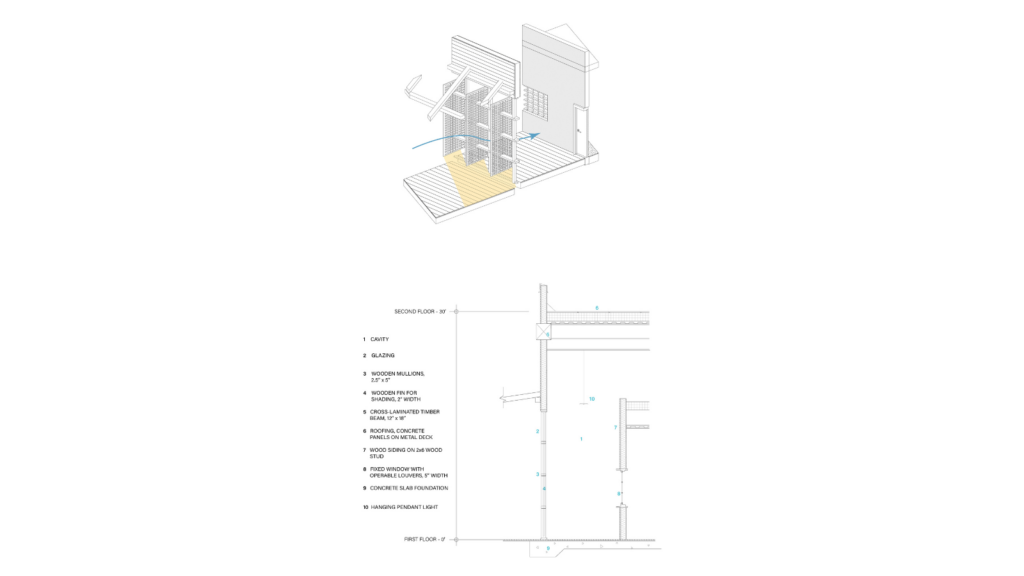

As visitors move through the community center, the wall separates and opens access to spaces by the use of an arch form. One of the main programmatic elements is the Korean garden, an opportunity to showcase vegetation unique to Korea, as well as traditional Korean garden design. The garden follows the wall throughout the project, weaving through the middle space producing a soft and serene area for people to walk through. With the addition of the wooden structure one can almost visualize a quiet village around the garden.

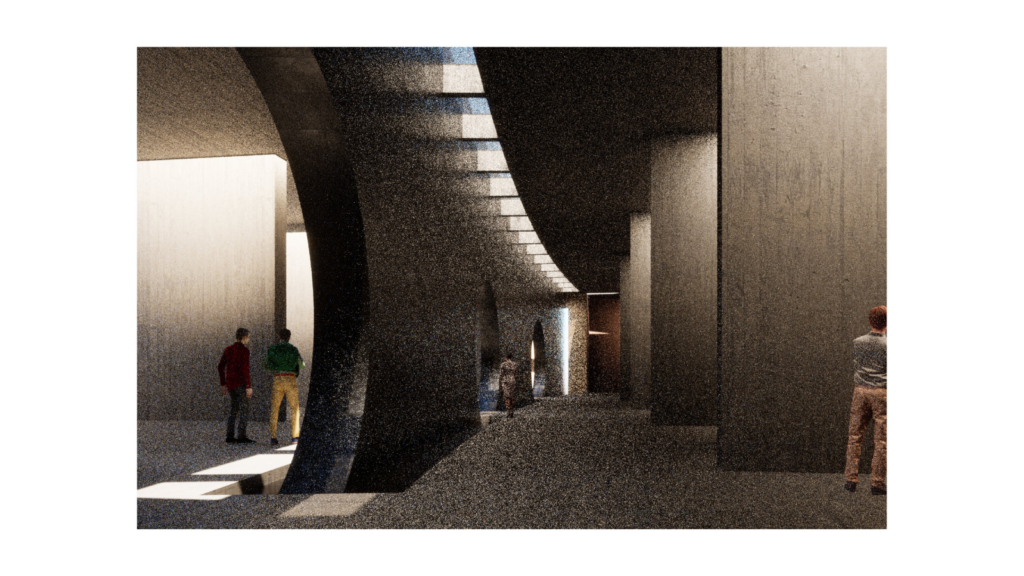

The next sequence is the museum exhibitions, at first invisible from view because of the curved organization of the architecture. Upon entering the exhibit, the architecture appears harsh and guttural, elements pulling apart from each other, and the wall is pierced by circular voids. This expression suggests a somber tone as the visitors learn about Dosan and the calamity of his life when advocating for Korean independence from the Japanese. Finally, the visitors reach the end, a circular platform showing views of the city and the reservoir landscape, where visitors can reflect on the work of Dosan.